Go to Whole Earth Collection Index

by Robert Horvitz, 29 January 2019

RH: So, John, have you finished your book?

JM: Oh, god no. I am in the midst. I would say I'm about one third. It's not linear, so who knows. I'm writing.

RH: If you're following Stewart's life chronologically, and if you think you are a third of the way, does that mean you're up to his late 20s?

JM: [laughs] I'm writing more or less chronologically. When you're writing a biography you more or less have to, unless you're being really arty. I think the final manuscript is going to start somewhere in the middle of his life and then go back to his childhood, which is a device often used by biographers. So Stewart has just gotten out of Stanford. He graduated in the summer of 1960 and then joined the Army, spending a little less than two years mostly on the east coast. He was trained at Fort Benning. He started with great optimism, but then he washed out of Ranger training, which was one of his big failures in life. He did fine in the airborne training, which was parachute jumping, and then was made a basic training instructor at Fort Dix in New Jersey, and he was very unhappy about that. It was not what he wanted to do, and he basically spent the rest of his time trying to find something interesting to do in the military. Without success. It was peacetime military. That's what I'm writing about now.

RH: I would guess that since you know what happens later it must be hard to stop that knowledge from seeping into your description of the earlier stages. You don't want to make things seem predestined.

JM: One of the themes I am trying to capture is that things bubble for Stewart for a long time. Sometimes decades earlier you'll find threads of things that will blossom later. That makes it easier in some ways: you can foreshadow things. I wrote three chapters about Stanford because lots of things that were a big part of his life were emerging then. Going back even earlier, Stewart makes a big deal out of taking a Conservation Pledge at age 7. That's a filter through which he still sees alot of his life. You can go from the Conservation Pledge to Revive and Restore and its part of the same cloth.

RH: Stewart has been written about so much, have you found some fresh earth to turn over?

JM: Where I want to situate Stewart is a little bit different than the stuff that's come before. My working subtitle for the moment is Stewart Brand and the Creation of a California Century. My argument is that Stewart was instrumental in the set of events, the arc, that led to this particular California sensibility or worldview that went on to infect the entire world. And in some way, politics in America today echoes what he was involved in creating.

RH: Do you have a deadline?

JM: I had a deadline last fall, but these things are always variable. They seem to have patience with me.

RH: If your deadline was last fall they probably wanted to publish around the Catalog's 50th anniversary.

JM: Actually, no, they were not that bright. There is a group making a documentary about Stewart now. They say they're committed to January of 2020 for introducing their movie. I was hoping to have the book come out at about the same time as the documentary, but if they hold to their schedule, there's no way I'm going to make that. My goal is to have a manuscript this summer. That'd be great. That'd be a two and a half year project. I started at the end of 2016.

RH: Are you enjoying the writing?

JM: Yeah, but I'm in that period where there's more writing ahead of me than behind me and I still don't know what I've got. I think I'm going to forward-load things in the sense that if you look at the arc of Stewart's life, he's been much less peripatetic in the last 20 years than he was before. He used to put things down and go on to the next thing relatively quickly. His books came out in a compressed period of about 10 years and then, I wouldn't say he's slowed down, but rather he's focused. Long Now and Revive and Restore are really interesting projects but it isn't clear what their impact on the world is yet. Whereas you can go back to the 1960s and see what his impact has been. So the book's going to be forward loaded in that sense. At least that's my plan.

RH: What has surprised you most in researching his life?

JM: What surprised me most about Stewart Brand. He had a really hard time in parts of the 60s and 70s. People know about his accomplishments in that period but he put the Whole Earth Catalog together largely because he was having a nervous breakdown and his marriage was falling apart. That's going to be hard to write about. It was a very difficult time for him. He was considering suicide and he was brought out of it by a relationship.

What's most surprising about Stewart. That's a tough question, maybe because I'm so immersed. I'm writing while still doing research. I'm going back to the library to look at things again. I don't know if I told you about this before but Stewart gave his papers to Stanford in 2000, and I was in there with Fred Turner - we were both in there looking through them in 2000 and 2001. And his journals were there at that time. At that point I was looking for something very specific. I was curious if he had written anything about Doug Engelbart around the time of the demo but he did not write about that. He was using his journal to write about his relationships and how unhappy he was. I noted that at the time but didn't make much of it. He has a very detailed description of his first LSD trip in 1962, and that's what I included in Dormouse. But I went back in 2016 and the journals were no longer there. The Library had meticulously photocopied them all and redacted the names of his various girlfriends over the years - for what reason I could never get out of them. And they hadn't told Stewart they'd done this. When Stewart confronted Mike Keller, who is the head librarian, he said we're doing this to protect you. And Stewart said, protect me? I'm 80 years old! And so they immediately put the journals back in. Which was great, except that I'd gone through the redacted texts and now I'm going back again if I need to, but it's kind of a pain in the neck.

RH: This information about Stewart's depression when he was creating the Catalog, that's news to me. I guess it's old news to you because you discovered it almost 20 years ago, right?

JM: Well, yeah, and we talked about it alot since. In addition to doing the library research, I spent probably a year and a half going to visit him in Sausalito every week. I became his therapist in a way. We're still doing that. Because in this modern era, if I find something in his journal I can send it to him and ask him what he thinks, to get perspective. It's really an interesting way of trying to piece a life back together.

RH: How would you describe his state of mind now?

JM: Quite remarkable. I see him regularly because he's still very active in many different ways. He's the interlocutor for the Long Now events and he shows up for things regularly. But he's slowing down and I find his memory of things 50-60 years ago to be maddeningly vague. He was at the Interval last week with Zander and Kevin Kelly talking about their trip to Siberia, which they did at the behest of the filmmakers, to Pleistocene Park. And Stewart was great: very articulate, laying out the argument that Revive and Restore is making. He does it like a guy of 60, not like a guy of 80.

RH: Who are you writing this biography for?

JM: Penguin is my publisher.

RH: I meant who is the audience?

JM: That's always a challenge. It's a challenge even when writing for the New York Times. I think in a sense this book is for me as much as it is for anyone else. I followed along in Stewart's footsteps about a decade after him when I was growing up. I watched what he was doing, as he was doing it, going all the way back to when I was in college and saw the Whole Earth Catalog and the Truck Store in Menlo Park.

RH: If you thought you were following Stewart's footsteps, the possibility of this book must have occurred to you a long time ago.

JM: He was a reference point but I have very different politics than Stewart does. He has this weird blend of conservationism and conservativism, and I grew up as a "red diaper baby." In trying to understand Stewart, Fred Turner makes a big deal of his anti-communism. He sees that as a motive, which I think is not completely accurate, although I've read the same journal entries that Turner focuses on, and I even found an article that Stewart wrote for one of the Stanford student magazines (called The Bridge) titled, "Why I Stand Against Communism," which nobody had seen and Stewart had completely forgotten that he'd written. There was a long period when he was a libertarian and for him that was all about personal freedom: "ask not what you can do for your country, ask what you can do for yourself." But I don't think his was textbook anti-communism, in the sense of the John Birch Society. It was really shaped by knowing someone in his college dorm who had fled from Hungary in response to the Soviet occupation. When the Russians invaded in 1956, he was there before coming to Stanford. His dorm mate's experience influenced Stewart's view of communism more than the philosophy. And you can dial that all the way forward, through that period when he was preoccupied with personal freedom. But then Stewart's worldview really changed when he spent a year in Jerry Brown's office in 1976. He decided then that there was value in good government, which is not at all the view of a libertarian. Stewart's politics after the year with Brown is harder to pin down. It's not easy to define. He says he walked away from the environmental movement, but at the same time he's pro-nuke because he wants to save the world from climate change. So it's complicated.

RH: I was trying to find out how and when the idea for this book came to you.

JM: Oh. It was actually Kevin Kelly's idea. Stewart had been thinking for a number of years about writing an autobiography and then he decided he just didn't have enough energy for the project. He's close to Kevin and Kevin said, well, we should find a biographer for you. And Kevin came to me and said would you be interested. I was looking for a way out of the New York Times at that point. It was because of the events that made up Stewart's life that I got interested in the project. In my mind I saw it as a sequel to the book I wrote called What the Dormouse Said which really focused on things that happened around Stanford between 1965 and 1975. This sequel is a bigger way of getting at some of the same things, trying to understand that mix of economics, politics and culture that came out of Northern California. Stewart was very much at the heart of that mix.

RH: When did this conversation with Kevin happen?

JM: It was in the late summer or fall of 2016.

RH: So this project didn't start bubbling long ago.

JM: No, not at all, I'm not like Stewart in that way. I'm much more opportunistic. Although I've been very interested for a long time in the meta-question about this region that I grew up in, Stewart found a home here and that made his life a great way to explore that subject. But it took me a while to leave the paper so I didn't really start the writing until January 2017.

RH: Kevin didn't want to write Stewart's biography himself?

JM: I never asked him. I think he sees himself as a friend of Stewart's and that would make for a conflict of interest.

RH: Or a big advantage.

JM: It's possible. Kevin has a current book project but he told me at one point, after his last book, that he wasn't going to write books anymore.

RH: Stewart must feel almost trapped by his reputation, because I'm sure he's asked the same questions about his past, over and over again. Crumb told me that almost every interviewer asks him the same questions and it's been that way for decades.

JM: Stewart enjoys the attention. He's never shied away from being a minor celebrity. One of the things I collected was all the profiles that have been done on him over the years. The best one was by Katherine Fulton in the Los Angeles Times. But there are many versions over many years and he's always very cordial. People still want to sit down with him but I think he's avoiding them now. The other thing that's happened, I don't know if you saw the piece The New Yorker ran.* It was by and large a nice piece but then there was this weird coda at the end where the author decided to take a shot at him and blame him for everything. That's in fashion now. The bit has flipped. The zeitgeist has changed and Silicon Valley has gone from being able to do no wrong to being able to do no right. And in the hunt for the guilty parties, things go back to Stewart. Franklin Foer** blames him. Jonathan Taplin*** doesn't blame him but they both trace digital libertarianism back to Stewart. I actually think that's wrong but that's another story. That's certainly the common view.

RH: This affects what you're trying to do, which is to put Stewart into context. Do judgments like that complicate your task or hem you in?

JM: I feel frustrated. There is a view of Stewart that was captured first by Fred Turner, in From Counterculture to Cyberculture, which is actually different from the portrait of Stewart that I drew in What the Dormouse Said. I think Stewart was in many cases the first observer. He was working in that period as a journalist and was one of the first guys to figure out what's happening. Turner, on the other hand, views him as a protagonist. I think some of that gets overstated. If I had to pick the birthplace of digital libertarianism, I wouldn't put it at the WELL. I'm not going to fight that battle in this book. I do have a view on the influence of the WELL and where to place it and it's different than the popular conception.

RH: Where would you place it?

JM: Do you know about Usenet?

RH: Sure. I wrote about it for Whole Earth.****

JM: I would place it in that unorganized, geographically distributed unity of hackers that took form in the structure of Usenet. I was around for the start of the WELL, and one of Stewart's most brilliant moves was that at the very beginning of the WELL, he gave people like me and Steven Levy and all the so-called tech writers free accounts. And so we all hung out there. And as a result, the WELL got a magnified image in the world. It's influence appeared to be outsized. That's my sense. You were online in the mid 80s, weren't you?

RH: I was. I had Internet access very early and was on The WELL from the start, too.

JM: Online discussions were bubbling up all over the place. It happened that the DeadHeads did end up coalescing at the WELL, but I actually think that digital libertarian culture was much more diffuse.

RH: I agree.

JM: Stewart captured it very early on, with the Rolling Stone piece in 1972. That was a very significant piece for me. That was one of the things that alerted me to the fact that a new tech culture was growing out there.

RH: You just reminded me of a piece that had a similar impact on me, which you may well know: Ron Rosenbaum wrote about Captain Crunch and "blueboxing" for Esquire in 1971.

JM: Of course!

RH: I was so impressed that someone my age had an article in Esquire that was totally brilliant and original - and then I met John Draper [Captain Crunch] right after he got out of prison.

JM: That article had that kind of influence on me, too. One of the things I stumbled across, talking with Stewart, that neither of us has written about anywhere: he was blueboxing in his dorm room at Stanford in 1956! It was simpler technology then. They were just shorting out a resistor. They didn't have a box, but they were able to make free phonecalls and that was routinely done in dormitories all over the country.

RH: You must have asked Stewart how he sees his place in history, no?

JM: No I haven't. You've given me a question to ask. We've talked about specifics but I haven't asked him to stand back and comment on the big picture. And I haven't asked him about my central thesis. I should. But we have talked about the impact of various things that he did. For example, we have a big disagreement about the impact of the Life Forum that Stewart organized at the UN Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972. It was one of the few directly political things that he's done and he considered it an abject failure. He wanted it to be WoodStockholm but nobody showed up. They had this village outside the city where they were going to have an encampment of what he hoped would be hundreds of thousands of people and he got hundreds. It really turned him away from activism. He became very pessimistic at that point. And yet as political propaganda it had much more impact than he realizes. Wavy Gravy and the Hog Farm came along. Stewart paid for them to bring a couple of buses over there. And they outfitted one of the buses as a whale and they had a parade one day and a photo of that whale bus showed up on the front page of every newspaper in the world. And that led to the Save the Whales campaign, which has been pretty successful so far.

RH: I'm not surprised he's been disappointed in some of his undertakings because he has generally high ambitions.

JM: Stewart really doesn't believe in activism in the streets. He believes in science. And yet he has been an activist at various points in his life.

RH: So, John, what's next? Do you have a project after this book?

JM: What's next for me, I think, is to decide if I still want to be a journalist after this book. I am enjoying this project but one thing that frustrates me is that I still haven't gotten the New York Times entirely out of my blood. I still work for them occasionally. Over the last two years I've written for them a number of times. I'm still free-lancing. The question is do I want to continue working as a journalist or is it time to go off and do something else. I haven't figured that out yet.

RH: Would your decision be based on a tech story that piques your interest, or change at the Times?

JM: When I left the paper, what I was just starting to do was report about Cambridge Analytica and I really regret not being able to pursue that. I think my instincts were correct, but I dropped it. I'd written some pieces about fake news and on bots and thought those were really important stories. I'm always interested in the impact technology is having on society. When I came to the paper in 1988, technology coverage in the Business section was rich and broad. There were seven people focused on different kinds of technology, only one or two of them being information technologies. Information technology seems to have eaten the world and that's not good. These days in terms of my own intellectual interests I'm mostly interested in material science. That would be fun to write about, because I see so many remarkable things that are going to have an impact on the world - energy is one, and batteries for example. But I don't think the paper is paying attention to such things in any systematic or thoughtful way. They're just following the money.

RH: So are you looking for a new platform that's more interested in technology?

JM: That's an interesting question. The door at the Times has remained open and it's such a good platform that I think if I'm going to do journalism, I would go back there, although it might be fun to lift my head up and look around and see what else there is to do for a while. I haven't done that for a long time. I will be seventy years old this year so I'm not sure I want a second profession. I can't conceive of what I'd do besides writing. I began as an activist and I look at the political situation in America as an incredible train wreck but I'm not sure I want to be involved politically. I probably should be but I haven't found any way to make a livelihood out of that. I'll just wait and see. This book project may go on for longer than I expect. I'd always finished my books quickly so I could go back to my day job but now I have no day job to go back to.

RH: Work on the book is expanding to fill the time available?

JM: Yeah, absolutely. I get that feeling that's what's happening. Plus it's nice not having to rush through it. My commitment is to having a manuscript by next summer, not a finished product.

RH: Since the work is expanding to fill the time available, it might be interesting to do a really huge multi-volume portrait of Stewart. I'm sure the richness of his life would justify it.

JM: There's that richness there, but the New York publishing industry sees Stewart as what my friend Greg Zachary refers to as a "major minor figure." I don't have a contract to write a multi-volume biography of Stewart. It's a more modest project. That's why I'm thinking about Stewart Brand: The Early Years more or less.

RH: Really? is that all you'll cover?

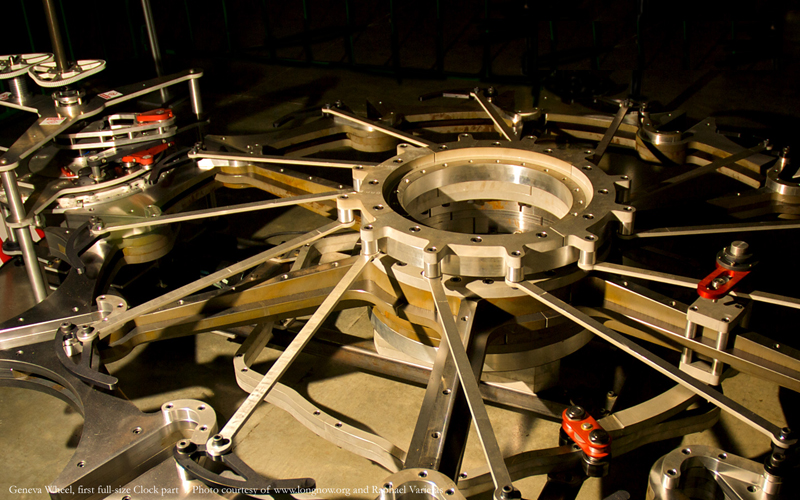

JM: Well, I told you it will be front loaded, but no. I'm going to try to capture his whole life, but I'm focusing on the period up to when he wrote his books. Maybe this is wrong but I'm really seeing the Clock of the Long Now and Revive and Restore as a coda, even though they've been going on for 20 years. It may take us centuries to figure out what the impact of the clock is. You know, I got to visit the clock with the film crew and it really is an extraordinary monument.

RH: Do you believe that it can last 10,000 years?

JM: I have no idea. Things get vandalized, right? What if society breaks down in 500 years. Many other empires have fallen. There's no serious protection for the Clock and you can imagine it being stripped like an Egyptian ruler's tomb. Or you could see a scenario where it becomes a religious mecca and people come to venerate it for centuries.

RH: Some group will probably claim that it was created by aliens. Does the clock have a warranty?

JM: [laughs] Danny says that he has tested all the components to be sure they'll last for 10,000 years. But when you look at it, it's an extremely complex mechanical thing.

RH: That's why I'm asking if it will really last that long. Wouldn't it have a better chance if it was simpler? I guess what I'm really asking is: is there a reason for the complexity? I can't see why it needs to be that complicated.

JM: It's a good question. I haven't had that conversation with Danny. Is it the appearance of complexity or actual complexity? I really don't know. I just know it's a beautiful machine, remarkable in both scale and imagination. But when I tell people about it, they usually say there are much better things to spend money on than a 10,000 year clock.

* Anna Wiener, "The Complicated Legacy of Stewart Brand's Whole Earth Catalog," The New Yorker, 16 November 2018.

** Franklin Foer, World Without Mind: The Existential Threat of Big Tech, Penguin Press/Random House, 2017.

*** Jonathan Taplin, Move Fast and Break Things, Macmillan, 2018.

**** Robert Horvitz, "The Usenet Underground," Whole Earth Review #65, winter 1989.